That’s the findings of some recent research and the goal of U.S. drug czar Michael Botticelli.

“Research shows that the language we use to describe this disease can either perpetuate or overcome the stereotypes, prejudice and lack of empathy that keep people from getting treatment they need,” Botticelli told The Huffington Post. “Scientific evidence demonstrates that this disease is caused by a variety of genetic and environmental factors, not moral weakness on the part of the individual. Our language should reflect that.”

He said that along with greater prevention and treatment efforts, “reducing the stereotypes and prejudices associated with substance use disorders” is a key element of the Obama administration’s approach.

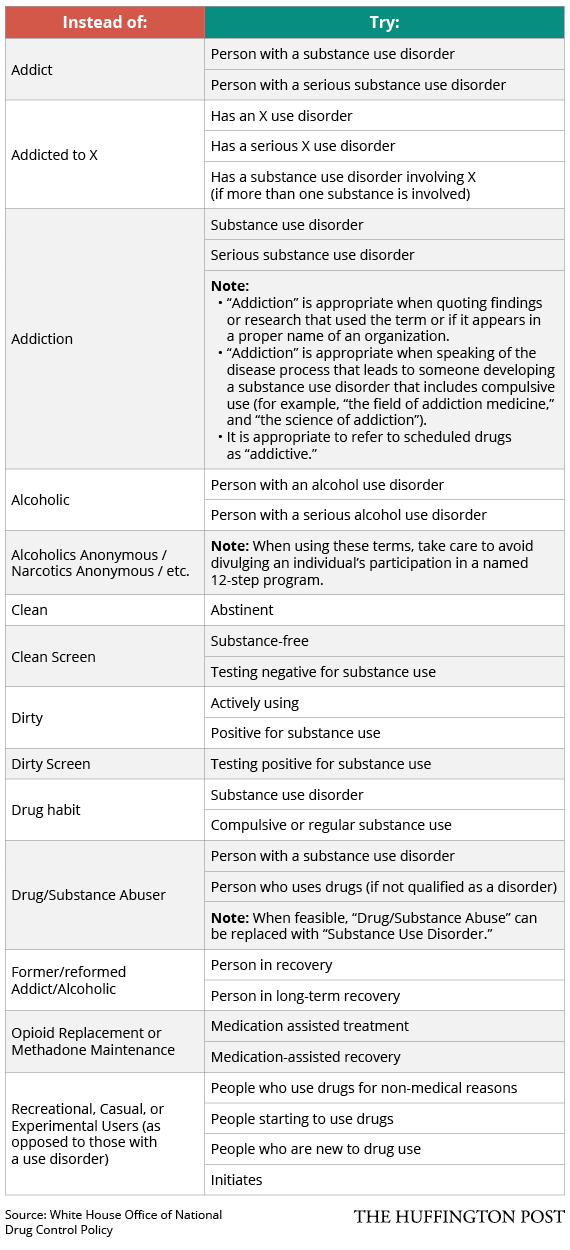

With that goal in mind, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy has drafted a preliminary glossary of suggested language. The drug czar’s office recommends replacing the word “dirty” for example, with “actively using,” or “clean” with “abstinent.” Even basic terms like “addiction” and “alcoholic,” which people may not necessarily associate with prejudice, should become “substance use disorder” and “person with an alcohol use disorder.”

While the glossary is still being developed with no final deadline, the Office of National Drug Control Policy shared a working copy with HuffPost:

“This change goes beyond mere political correctness,” said Dr. John F. Kelly, associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School who has been working with the drug czar’s office on reforming the language of drug use. “Whether we are consciously aware of it or not, the language we use actually makes a profound difference in our attitudes and, thus, how we may approach our nation’s number one public health problem,” he told HuffPost.

Kelly explained that addiction affects the brain’s “neurocircuitry of reward, memory, motivation, impulse control and judgement.” Areas of the brain that allow an individual to curb impulses to use alcohol or other drugs are severely compromised.

“Use of terms more in keeping with this medical malfunction, such as describing an affected person as an individual with, or suffering from, a ‘substance use disorder’ — as opposed to a ‘substance abuser’ — may decrease stigma and increase perceptions of a need for treatment,” Kelly said.

His own research has found that the way a person is described produces meaningful differences in how that person is judged. A 2009 study by Kelly and his colleagues asked people to read two randomly assigned passages identifying the same individual as either a “substance abuser” or “having a substance use disorder.” Participants who read the “substance abuser” language, even those who were mental health or addiction specialists, tended to see that individual as engaging in “willful misconduct” and constituting a greater social threat.

Such views “can increase perceptions of the need for punitive action,” Kelly said. “We have seen this played out to a certain degree in the increase in our drug-offender prison population,” he added.

The United States is home to just 5 percent of the world’s population but a full 25 percentof the world’s prisoners. That is due in part to the harsh sentences handed down for nonviolent drug possession and distribution crimes. In 1980, there were roughly 40,000 drug offenders in U.S. federal and state prisons, according to research from the Sentencing Project. By 2011, the reform group reports, the number of drug offenders in prison had ballooned to more than 500,000 — most of whom were not high-level operators and did not have prior criminal records.

“Growing up, we all heard and sometimes voiced the childish refrain, ‘Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me,’” Kelly and his colleagues wrote about their study. “But words can and do hurt, and in ways that we are not aware and cannot always anticipate.”

Millions of Americans meet the criteria for diagnosis of substance abuse or dependenceand could benefit from treatment. According to 2012 data from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, nearly 24 million Americans age 12 or older had used an illicit drug or abused a medication in the previous month. Some 23 million needed help with a drug or alcohol problem, yet only about 2.5 million “received treatment at a specialty facility.”

To lower the barriers to seeking and getting help, Kelly and other researchers are calling for more medically appropriate language that conveys the same dignity and respect offered to other kinds of patients.

As Kelly and his colleagues put it, “We should stop talking dirty.”

Source: Huffington Post